Written by Perry Firth, graduate student in Seattle University’s Community Counseling program; graduate assistant, Project on Family Homelessness

What would it be like if you lost your home to foreclosure? Who would take you in? What does it feel like to tell your children that there will no longer be running water in the home, and that for the foreseeable future, all of the household’s water will be retrieved from buckets in the backyard? How do children feel watching their parents struggle to make enough money to eat, and fight off despair when they are unable to find a job?

These are the types of questions that many of us never ask. For those of us who feel securely middle class, the idea that a family would retrieve water from a bucket in the backyard, or go without food so that their children can eat is unthinkable. Decisions like that belong to “other people,” maybe in other countries, separated from us by the insulation and distance provided by money.

Unfortunately, there are many people who know the answers to these questions. They know what it is to live with reminders of the American Dream and signs of affluence all around, yet feel that they are living in a separate America. In this America, hunger is normal, poverty is real, and joblessness feels permanent.

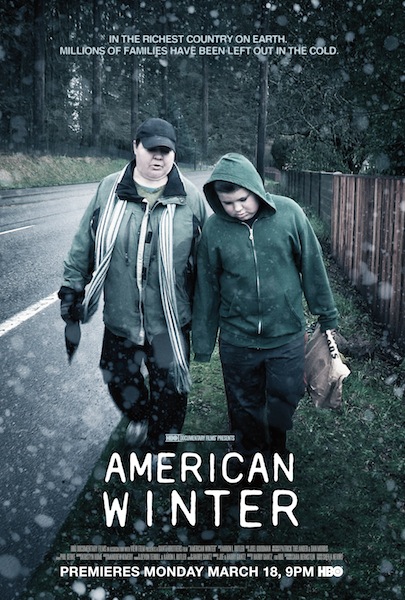

The experiences I outlined above were drawn from Joe and Harry Gantz’s latest film, “American Winter.” In this documentary, the harsh realities of living with poverty in America are shown through the lives of eight Portland, Oregon families found through Portland’s 211info resources and housing system. While each family is unique, the barriers they face as they look for jobs, try to secure housing, or make ends meet on minimum wage are not.

Filmed in Portland during the winter of 2011-2012, “American Winter” is getting the kind of attention that most documentary films about homelessness typically go without. The reason for this is clear. Through the lives of the families captured on film, the increasing vulnerability of the middle and working classes is brought to life, and the human ramifications of a weakening social safety net are revealed in all their painful detail.

In fact, part of what makes “American Winter” so powerful is that it is impossible to escape the uncomfortable reality that the poverty affecting the families in the film is also affecting millions of others.

“American Winter” premiered on HBO in March, and will be available on DVD this fall. The co-director Joe Gantz has been traveling with the film and partnering with various organizations to screen the film and raise awareness about poverty and homelessness in America.

On Tuesday, June 18, I joined an excited audience at SIFF Cinema Uptown in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood for one of these screenings. It was hosted by the organization I work for, Seattle University, in partnership with the Washington State Budget & Policy Center and Working Washington. Thirteen other organizations, including Firesteel and YWCA Seattle | King | Snohomish, were so supportive of this film that they joined us as co-presenters.

What I found powerful about the film is that regardless of your political orientation, seeing children go hungry and talk frankly about how cold it is in their house in the winter, or a father describe his increasingly low self-esteem as he is unable to provide for his family, forces us to analyze how we speak of and deal with poverty in America. In this way, the documentary portrays what the politics of poverty often obscure: the people actually trying to get by on nothing.

The families that made this film possible

The filmmakers found the families by working with the 211info system in Portland. They initially interviewed 100 families for this film; however, the final cut featured these eight families:

- TJ and Tara and their three children. When TJ loses his job, Tara’s minimum wage job is not enough to keep the family stably housed and fed, even though she is working a 12- to 13-hour day and skipping lunch.

- Single father John, and his son Geral, who has Down syndrome. We meet John after he has been unemployed for three years after losing his middle-class job. Now his house is in danger of foreclosure.

- Ben and Paula and their two sons. They were living a comfortable-middle class existence till Ben lost his job, and their house went into foreclosure.

- Brandon, Pam, and their two sons. When Brandon loses his job, the family is forced to move into the two-bedroom apartment of Pam’s mother.

- Single mom Diedre and her four children. Diedre’s college education and prudent career choices are not enough to save her family from poverty after she is laid off from her medical technician job. She ends up donating plasma and collecting scrap metal to make ends meet.

- Single mom Shanon. She faces financial insecurity after her daughter Chelsea, 12, needs months of medical care for a stomach condition. Ultimately, she ends up with a $49,000 medical bill that she cannot pay.

- Mike and Heather and their five children. When Mike loses his job, the family must go without heat, water and electricity. The parents worry their children will be taken away because of their inability to provide basic necessities.

- Single mom Jeannette and her son Gunner. They cope with homelessness after the death of Jeannette’s husband. They end up in an unheated, windowless garage, and then a shelter.

The screening of “American Winter” clearly moved the audience, but what made it all the more powerful was the attendance of some of the families featured in the film; the presence of co-director Joe Gantz; and the poverty and homelessness policy discussion after the film.

The post-film policy discussion

The policy discussion centered on many of the obstacles faced by the families in the film, like the erosion of the safety net, the increasing fragility of the middle class, the challenges faced by trying to survive on minimum wage, and the widening gap between the affluent and the poor.

Moderating that night was Alice Shobe of Building Changes. The speakers were Lori Pfingst, senior policy analyst with the Washington State Budget & Policy Center, and Marilyn Mason-Plunkett, President/CEO of Hopelink.

The sort of obstacles holding so many families in poverty, and the level of poverty now being seen in America, were further illuminated by statistics like these, presented by Lori Pfingst:

- In pre-recession Washington state, there were 700,000 people living poverty. Now, post-recession, there are 200,000 more.

- About one in six Washingtonians lives in poverty.

- The federal poverty guideline for a family of four is $23,550. This means that if you earn $23,551, you are above the poverty line.

- Lori said that a more accurate poverty line for Washington would be $46,000 for a family of four. By this more accurate definition, one in three people in Washington state live in poverty.

- While business profits have continued to grow, median income has stagnated since the 1970s.

- For a family of three in King County to do more than just make ends meet, they would need to earn between $57,000 and $59,500. Unfortunately, only three in 10 jobs actually pay this much in King County.

All of these statistics are troubling, but the one I find to be most infuriating is that the poverty line for a family of four is $23,000. That amount is hard for one person to live on, much less four people. Unfortunately, statistics like this show the uphill battle poor families must face as they try to make ends meet, especially as there are many federal programs that use the poverty level to determine whether or not a family can receive government assistance. This means that a family of four earning $27,000, for example, would be ineligible for some federal programs because, well, they are “not” in poverty.

Clearly, “American Winter” is timely. But as many in the audience said, and as the policy discussion revealed, the stories shown in “American Winter” need to do more than just move us. They need to motivate action – and if not, as one audience member pointed out, their stories have been in vain.

A movement for the middle class

Along these lines, co-director Joe Gantz called for a “movement for the middle class.” It is stronger than what one person could do alone, he said, and would pull from a broader base than those already committed to fighting poverty; what we need is a movement to empower the working poor, and strengthen the middle class.

As to what would be involved in this movement, common themes were clear in the ideas brought up in the policy discussion. Among these, investing in education, fixing America’s healthcare system, and strengthening the social safety net were mentioned as ways to bolster the middle class and ensure that the social mobility essential to the American Dream remains.

This call for a movement for the middle class may seem like a challenge. After all, don’t movements require a lot of work, organization, and time? To that I would respond that a movement is, at the end of the day, no more than a group of concerned citizens committed to doing their individual small part in creating a more equitable society. With this definition in mind, a movement becomes manageable, and your contribution feasible.

Ways to contribute to the “movement”

Here are some things you could do to ensure that the stories told in “American Winter” aren’t in vain:

- First, see the film. You can attend a free screening at Bellevue Arts Museum on August 17 hosted by Imagine Housing, Eastside Baby Corner and Leadership Eastside. Film DVDs are available for pre-order on the “American Winter” website. Subscribers can also view it on HBO GO, or request to host a screening.

- Host a screening of the film. Contact the filmmakers at www.americanwinterfilm.com.

- Read about homelessness and poverty in America. Learning is a huge part of advocacy. We cannot change what we don’t understand. Here are some great sites: “Poverty in America,” “U.S. Poverty by the Numbers,” and the National Center on Family Homelessness.

- Talk about these issues in your community. Organize a community screening of the film. Bring up poverty and “American Winter” in church.

- See “Poor Kids,” another powerful documentary on poverty in America. It is free on the PBS website.

- You can also contact your legislators, and let them know that you prioritize investing in the middle class and making policy decisions that benefit the middle and working classes.

America continues to face an uphill battle as government spending continues to be cut and jobs outsourced, and middle income jobs become increasingly hard to come by. With more than one million school-age children now homeless, the highest number ever reported, and family homelessness rising rapidly, every voice is needed as America makes decisions on how to address the ongoing effects of the recession.

Did you see “American Winter”? What did you think about it? Leave a comment below.