Written by Catherine Hinrichsen, Seattle University’s Project on Family Homelessness

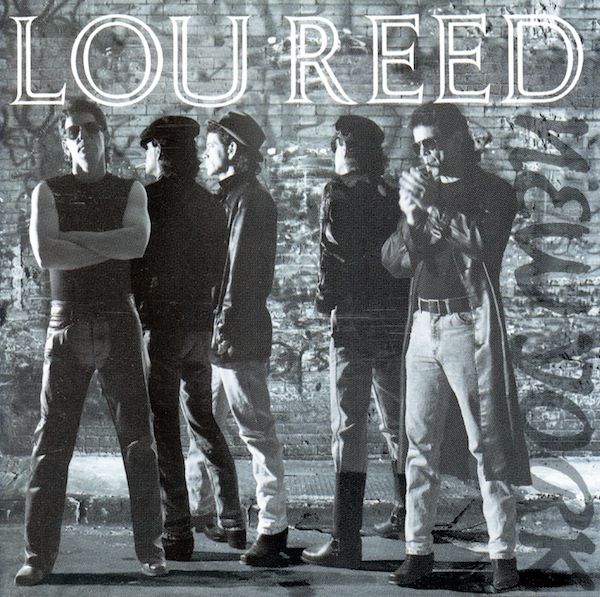

On his landmark 1989 album “New York,” Lou Reed told the story of a young boy living on the “Dirty Blvd.” The boy, Pedro, exists in miserable poverty, and is beaten regularly by his father “’cause he’s too tired to beg.” But Pedro still has dreams. Yes, he dreams of “being older and killing the old man,” and he dreams of making himself disappear using a book on magic that he found in a garbage can. Above all, Pedro wants to “fly fly away… from that Dirty Blvd.”

You hear that and shudder. But what’s behind that song? It’s bewitched me for 24 years, but it wasn’t until a couple of years ago that I fully understood what it was about.

Like many others, I’m feeling nostalgia tinged with sadness as I reflect upon the loss of Lou Reed, who died a few days ago. It’s not only because an influential artist died relatively young. It’s because of the memories his songs evoke, and because he’s able to pack such potency into one three-minute rock song. With “Dirty Blvd.,” Reed wrote the soundtrack of family homelessness in New York in the late 1980s.

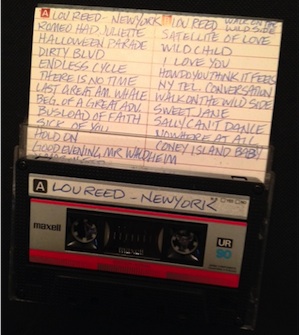

My sister introduced me to this album in 1989 via a cassette tape copy she made for me.

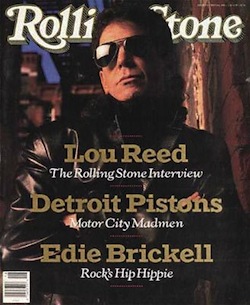

“New York” is one of Reed’s most acclaimed albums. Rolling Stone has hailed it as one of the top albums of the 1980s.

All these years later, it’s still one of my most-treasured albums, though now I listen to it on CD or my iPod. No matter what the format, the music is as raw and vibrant as ever, and the messages are just as poignant, hard-hitting and truthful.

My sister’s timing had been quite fortunate. I was just about to move to New York City for a job. Listening to this album was my prep. New York City in the late 1980s was kind of a mess, and Reed perfectly captured the city’s angst.

He pointedly and bluntly described what it was like to be living in New York at the end of the decade of excess. Rolling Stone reviewer Anthony deCurtis called the album “a rock and roll version of ‘Bonfire of the Vanities,’” referring to the 1987 Tom Wolfe novel that provided wry social commentary of late-‘80s New York (and another favorite of mine).

The city was reeling from racially charged tragedies like Howard Beach, Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Stewart and the Tompkins Square riot; watching young men die in droves from the burgeoning AIDS crisis; despairing at seeing Vietnam-era vets on the street; and reeling from controversies involving world leaders and famous politicians.

Reed memorializes all these signature events of the late 1980s. Disillusionment is all over this disc, especially when Reed refers to the “Statue of Bigotry” in not one but two different songs, pointing out the racial and economic disparities under the light of the torch.

“Dirty Blvd.” – the first song about family homelessness policy?

The album’s #1 single – and my favorite — was the song “Dirty Blvd.” The melody is simple; the chords are easy to play for beginning guitarists (G, D, A, D, repeat). The vocals are raspy, yet compassionate. The dynamics start quiet, then build to a volume of disdain. We meet a child and immediately learn of the deplorable conditions of his life:

Pedro lives out of the Wilshire Hotel

He looks out a window without glass

The walls are made of cardboard, newspapers on his feet

His father beats him ‘cause he’s too tired to beg.

On the surface, this seems like a song about extreme poverty and the hopelessness it engenders. Or perhaps it’s yet another condemnation of child abuse, a popular ‘80s theme (see Suzanne Vega’s “Luka” or 10,000 Maniacs’ “What’s the Matter Here”). It also draws distinction to class differences in this city with the greatest extremes in the world.

Outside it’s a bright night, there’s an opera at Lincoln Center

Movie stars arrive by limousine

The klieg lights shoot up over the skyline of Manhattan

But the lights are out on the mean streets.

A hard-hitting song, a memorable song; you listen and you feel bad for Pedro and all the poor children in the world.

But there’s much more to it than another sad story. Reed is railing against the policy that got those children into poverty and trapped them there like flypaper.

Pedro and Rachel: “Ain’t we the world too?”

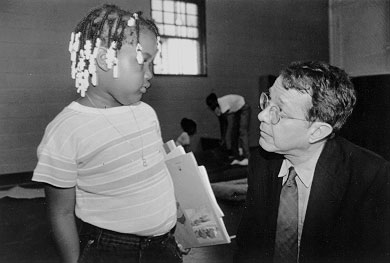

Just before this album was released, Jonathan Kozol published the astounding book “Rachel and Her Children” (1988). Earlier that year, Kozol had written a two-part series for The New Yorker, “The Homeless and Their Children.”

In both the articles and the book, Kozol describes New York City’s housing policy that plunged families into a never-ending mire of homelessness and desperation. This misguided approach culminated in multigenerational poverty, families torn apart and children thrust into foster care, chronic illness and even death.

Kozol was documenting the new phenomenon of family homelessness in America, which was unheard of before that decade. Families who had always been self-sufficient, and largely middle class, were beaten down by a system seemingly designed to rule out any chance of recovery.

The great irony is that the city’s solution was neither effective nor cheap. According to Kozol, there were nonprofits that operated excellent shelters for $34 to $41 a night per family, or roughly $1,000-$1,200 a month. (This is comparable to what my friends and I were paying for very livable midtown-Manhattan apartments.)

However, most homeless families were shoved into welfare hotels like the barely-habitable Martinique, which charged $63 a night for a family of four, and more for additional people. That meant $3,000 a month for a family of six – all sharing one stinking, toxic, rat-infested room where often the heat, plumbing or elevators didn’t work and there was no place to cook a meal for your family. Even venturing into the hallways was dangerous, so forget about a place for your kids to play. For this squalor, landlords could charge what they wished. The city paid one fourth, the state one fourth and federal funds the rest.

One of Kozol’s central subjects is Rachel, single mother of four — depressed, struggling to keep her family going and seemingly ready to crack. Rachel memorably refers to the invisibility of homeless families and the irony of Americans overlooking the great need right in front of them:

My children, they be treated like chess pieces. Send all of that money off to Africa? You hear that song? They’re not thinking about people starvin’ here in the United States. I was thinkin’: Get my kids and all the other children here to sing, ‘We are the world. We live here too.’ How come do you care so much for people you can’t see? Ain’t we the world? Ain’t we a piece of it?

It finally becomes clear

I wasn’t aware of all this at the time. Like many people in their 20s, I was more concerned with keeping up with my own bills, and dealing with the housing instability that comes with always-changing roommate situations.

So I only came upon “Rachel” a couple of years ago when I was learning about family homelessness for our project. Something clicked in my memory when I read this passage, in which Rachel’s nine-year-old daughter says:

“City and welfare, they got something going. Pay $3,000 every month to stay in these here rooms…”

$3,000 a month? That’s crazy! It sounded familiar. Then the lyrics of “Dirty Blvd.” came back to me:

This room cost 2,000 dollars a month, you can believe it man, it’s true

Somewhere a landlord’s laughing till he wets his pants.

That’s when it dawned on me. Pedro isn’t just an impoverished child; he’s one of “Rachel’s children.” He is a member of a homeless family. He’s part of a system built to guarantee that he has no chance.

Though I lived in Manhattan at the time, I had no idea there was such a thing as a homeless family, much less that the city was dumping money into ineffectual and unsuitable housing. Nor did I realize that the practice still goes on today, apparently.

Where are they now?

No one here dreams of being a doctor or a lawyer or anything

they dream of dealing on the dirty boulevard

At the time of “Dirty Blvd.” and “Rachel and Her Children,” there were fewer than 10,000 children and youth living in homeless shelters in New York City, according to the Coalition for the Homeless. In fall 2012, before Hurricane Sandy, there were almost 20,000. New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg raised ire last year when he suggested that the record increase of people in New York City’s shelters is because shelters are “much more pleasurable than they used to be.” A New York Times editorial of Sept. 25, 2012 said that “Advocates for the poor say New York City now has the highest number of homeless children since the Great Depression.”

And that was before Hurricane Sandy. Now, a year after that devastation, there are more than 21,000 children living in shelters in New York City.

What happened to children like Pedro and the real-life children of Rachel? Did they end up on the boulevard, perhaps even as parents of a homeless family? Just this week, The New Yorker published a lengthy report on the state of homelessness in New York during the Bloomberg regime, in which Ian Frazier writes, “the number of homeless people has gone through the roof they do not have.” It’s like coming full circle from “The Homeless and Their Children” – back almost to where we started.

But we can work to change all of that.

How we can change policy

On Nov. 5, New York City will elect a new mayor who may be able to apply more effective strategies to ending homelessness. In our state of Washington, we’ll elect our own local officials that day as well. That’s just one way we can work to change policy and help end homelessness and poverty. We can also:

- Urge our state legislators to make changes that can end homelessness, by joining events like the Jan. 28 Housing and Homelessness Advocacy Day in Olympia.

- Ask our local officials to increase funding for human services.

- Learn more about the link between the Affordable Care Act and housing.

- Encourage the use of solutions like Rapid Re-Housing that move families out of shelter quickly and keep them stably housed – at a lower cost than shelter.

- Keep talking about this. If you haven’t read “Rachel and her Children,” or the follow-up, “Fire in the Ashes,” do it.

- Listen to “New York” and feel the power of Reed’s work – it may spur you to action.

Did Jonathan Kozol’s work inspire Reed to write “Dirty Blvd.”? I’ve never been able to verify that. At one time, thinking about writing this piece, I toyed with the idea of contacting him directly to ask, my journalism training having instilled the need to confirm facts with the source. And now I’ll never have the chance. In fact, now, when I hear his grief-tinged “Halloween Parade” and the lyrics “This celebration somehow gets me down/Especially when I see you’re not around,” it will take on new meaning because now he’s the one who isn’t around anymore.

But I can still listen to his music and marvel at the power of art in engaging the public to end social injustice.